Finding truth in the era of memes

Written by James Murphy (opens in a new tab)

<p>We have access to more information than ever — why do we seem to be just as confused as ever about what is to be trusted? And where does accountability lie? </p><p>Trust is foundational to health. However, the media landscape today is extremely noisy, conflicting, and even downright chaotic. Memes are a biological response to help sift through noise — but without accountability, the most outrageous content wins, not the most accurate. How do brands and consumers, committed to health, best navigate this time? </p><h2>Our digital environment is full of noise.</h2><p>Much like processed foods are engineered to hijack our taste buds and keep us coming back for more, the media landscape today is designed to capture our attention (often through divisiveness and fear), creating a powerfully pro-inflammatory environment.</p><p><em>Anyone in the world can write anything they want about any subject, so you know you are getting the best possible information. - Michael Scott</em></p><p>The amount of conflicting information online creates what is neurologically referred to as “noise.” Confusing signals, or noise, creates uncertainty, which inhibits the brain’s ability to communicate accurately with the rest of the body.<strong> </strong><sup style="vertical-align: super; font-size: smaller;">1</sup></p><h2>Memes are a biologically efficient response to noise.</h2><p>Human biology is designed to optimize and make efficient information — from memories and pattern recognition to motor functioning. The current rise of digital memes can be seen as a neurological adaptation to the overwhelmingly noisy environment we find ourselves in.</p><p>Most folks are familiar with graphic memes — a photo with a caption slapped on that you reshare with friends. Memes have been circulating well before the social media era, though.</p><h2>Long before funny photos, there were memes. </h2>

<p>“Meme” comes from the Greek “mimeme,” which means “imitated thing.” Philosopher René Girard introduced mimetic theory in the 1960s, observing that human desire is largely shaped by imitating the desire of others — his career went on to expand on how that created conformity and competition for resources, power, and ultimately even violence. The biologist Richard Dawkins coined the term “meme” in his 1976 book <em>The Selfish Gene</em>, where he likened cultural evolution to that of genes, suggesting that ideas can spread from person to person analogous to genetic transmission. </p><p>TikTok made its business off memes, shifting the social media premise from “seeing what my friends post” to “showing me what’s trending.” Every platform has followed suit (Facebook, Instagram, YouTube thumbnails, Twitter, etc.). Meaning we’re seeing more memes in our media — catchy, click-bait content — than ever.</p><h2>This has downsides.</h2><p>Alarmist, inflammatory, or even just inaccurate content gets some of the strongest engagement — our biology is hard-wired to pay attention to fear. The engagement tells the platform to show it to more people. Twitter attempts to mitigate misinformation with “Community Notes,” and maybe AI will have some solutions for us soon, but right now, digital media is highly inflammatory.</p><p>In 2024, Jeff Bezos tweeted, <em>“Now lies can get ALL the way around the world before the truth can get its pants on”</em> about the falsely reported $600 million cost of his wedding. When someone is criticizing the cost of a wedding, the stakes are one thing when someone is terrorizing your health, that’s another.</p><h2>Reach is not the same as rigor.</h2>

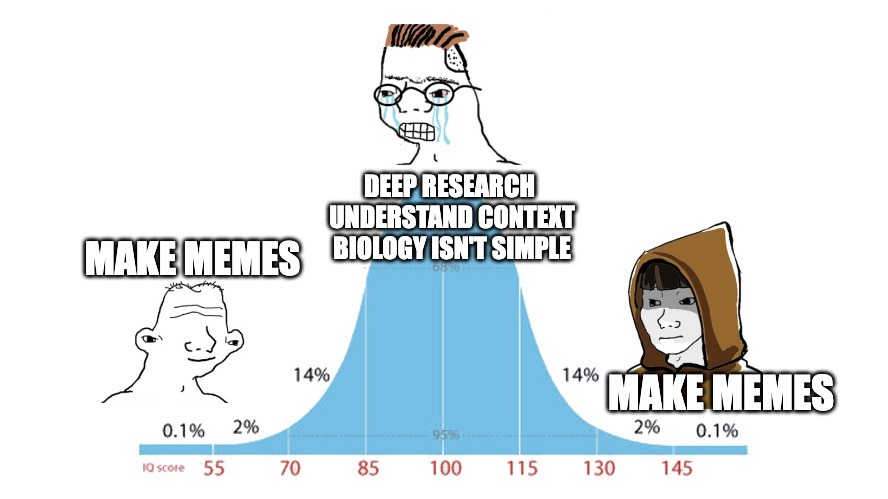

<p>Many health-related accounts hold themselves up as credible “influencers” or consumer watchdogs, without a basic working knowledge of how to read a lab test result or make conversions in the metric system. It’s my view that these accounts are terrorizing people and meaningfully causing harm to society (and, at times, good businesses). Within the digital context of “the most terrifying meme wins,” strong runway is given to the parasitic activity of this type of media.</p><p>Have you heard of the Ames Test? How about headlines like “a cup of coffee contains 0.45 mg of carcinogens”? Odds are, you’ve only heard the latter. Here’s how this connects: The Ames Test, developed by <a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bruce_Ames" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">Dr. Bruce Ames</a>2, was a simple, effective way to identify carcinogens. His research indicates that consuming these substances triggers a <a href="https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37939657/" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">hormetic stress</a>3 response that forces cells and organisms to adapt, making them stronger in the long run (resilience!). Further, his “<a href="https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1693790/" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">Triage Theory</a>”4 found that adequate nutrient intake is <em>protective</em> against a host of degenerative diseases, including cancer. All this remarkably changed our understanding of carcinogens.</p><p>Yet within months of releasing the test, the data was being taken out of context by the media to scare people and garner engagement — leading to those “coffee is carcinogenic" headlines. Dr. Ames spent much of the late part of his career devoted to helping people contextualize and understand that they need not worry about the carcinogens found in their food. </p><p>The Ames Test was developed in 1973. You don’t need me to tell you how much faster misinformation spreads (and warps) in today’s meme-driven, media landscape.</p><h2>A brief history of other previously inflammatory media cycles. </h2><p>With each new wave of technological advancement of media, society has gone through similar cycles. When the printing press was made so efficient that one person could operate it, pamphlet distribution soared – along with misinformation and gossip. This gave way to what became journalistic principles of verification. As radio broadcast its airways, similar alarmist and inaccurate media spread, leading to the Communications Act of 1934 signed by Franklin D Roosevelt and ultimately the FCC. It established electronic broadcasting as a public good and even limited the ability for foreign entities to own more than 20% of a broadcast network. Various supreme court cases reinforced the difference between the right to free speech vs the right to distribution of speech — such as Roth v. United States, 354 U.S. 476 (1957), which limits the distribution of obscene content. </p><p>Today, we are in another such time of media chaos, digitally. The recent censorship by government and tech on social media clearly isn’t the answer — however, we DO need forms of accountability on the social media airwaves. </p><h2>Accountability is key for health. </h2><p>Let’s connect this now to consumer goods. You need to know who makes your products and what’s in them — and hold individuals and businesses accountable. This premise was the foundation of trademark law, which largely came into form during the late 1800’s and early 1900’s with the rise of the then called “patent medicines.” These were drinks marketed for all sorts of health cures - the most well-known come from this era is Coca-Cola. Early patent medicines and their knock-offs would have dubious production practices and include all sorts of wild non-disclosed ingredients. The accountability around brand marks fortified much of the trademark system we still use today. Coca Cola even published their own 700+ page case law book and would send it to law firms to educate them. </p><p>Accountability is key for a healthy society — and applies both for brands and for digital voices - especially those holding themselves out as an authority. The keyboard warrior that parrots misinformation often does more harm to collective health by spreading anxiety than the imagined “good” of raising the alarm. </p><p>So how do we navigate a digital environment that holds little accountability and prioritizes sensationalized, memed content? How can we collectively work to provide calm and confidence in our trusted health sources and brands? </p><p>This is one of the challenges of our times. I don’t claim to have an answer, but I’ll share what we’re orienting around at LMNT.</p><h2>1) Prioritize long-form content. </h2><p>The foundation of our brand’s content is science-backed long-form; our focus started here, and it remains here. Long-form meets the type of customer that will read a blog or listen to a credible podcast — rather than jump from TikTok health news bite to news bite. It’s for the folks who commit their time to wrapping their arms around a topic.</p><p>It’s no coincidence that our objective statement is to “amplify a committed community of health seekers on a no B.S. rebellion to restore health through hydration.”</p>

<h2>2) Be rigorously succinct.</h2><p>Many topics take rigor and context to understand (the Ames test is just one example where knowing the context changes the whole story). However, we are also challenging ourselves to make some of LMNT’s key points and science more succinct. “Feel the difference” is one such meme. It’s an invitation to notice the impact when you take care of your health. It’s meant to prompt curiosity and to acknowledge the role electrolytes play in critical feedback signals we get from our body: fatigue, cramps, cravings, poor sleep, etc. Synthesizing complex information into accurate memes takes work. And while not as psychologically powerful as memes meant to evoke fear, these memes can help right a narrative.</p><h2>3) Expel parasites — trademarks and accountability.</h2><p>A brand mark (trademark law) is important for a reason. LMNT’s value as a brand is predicated on the integrity of trust and consistency we establish with our customer. We’ve started to see a growth in parasitic activity around our hard-earned brand marks — fake websites, attempts to extort us by registering our marks in other countries and having us purchase them, as well as trading on our trademarks with false claims for their own marketing. With this rise in parasitic activity, we’ve started to increase our rigor behind defending our brand mark and reputation. Building a reputation for enforcement also gives leverage for future situations.</p><h2>Maintaining trust in the era of memes.</h2><p>Trust is foundational to health. Trust in food quality, ingredient sourcing, and in the brands that</p><p>feed myself and my family. At LMNT we’ve planted our feet firmly in a stance for health — and</p><p>standing for anything, well, takes work. We don’t need everyone to use (or even like) LMNT —</p><p>but we sure as hell are going to stand for, and protect the integrity of, our product and brand. We’re better for it and so is our society.</p><h2>Responsibility lies with everyone. </h2><p>As a brand, this is a call to do some of our most rigorous work yet. I challenge <em>you</em> to do the work as well. As a consumer, do the research. Go to the source material before being quick to press a button and parrot an inflammatory post. For those with an influential platform: Resist the urge to promote inflammation by adding to the latest viral conflict. </p><p>For fellow health brands, we have a ton of work to do to move our space forward without tearing each other down in the process. We also have a duty to bring rigor to how we approach and calm our customers, rather than jumping at the “customer acquisition opportunity” bandwagon from fear. We’re working to improve our collective health — so let’s actually do it.</p><p>It’s rigorous work. It’s hard at times. Our health deserves it.</p><p><br></p><p>James</p><p><br></p><h3>REFERENCES</h3><p><sup style="vertical-align: super;">1 </sup>Referencing Peter Sterling and Simon Laughlin’s Principles of Neural Design: “Noise destroys information by introducing uncertainty.”</p><p><sup style="vertical-align: super; font-size: smaller;">2</sup> Wikipedia, "Bruce Ames" (2025)</p><p><sup style="vertical-align: super; font-size: smaller;">3</sup> Cheng et al., "Mitohormesis," <em>Cell Metabolism</em> (2023)</p><p><sup style="vertical-align: super; font-size: smaller;">4</sup> Ames, "Low micronutrient intake," <em>PNAS</em> (2006)</p>