How dehydration affects heart health

Written by Julie Stewart (opens in a new tab)

Medically reviewed by Ecler Ercole Jaqua, MD, MBA, DABOM (opens in a new tab)

<p><strong>Key Points: </strong></p><ul><li>Chronic, mild dehydration quietly increases the workload on your cardiovascular system.</li><li>Even mild dehydration reduces blood volume, forcing the heart to work harder to maintain pressure and flow.</li><li>When these compensations become routine, they add cumulative strain to the heart and blood vessels.</li><li>Electrolytes help keep water in the bloodstream, allowing the heart to move more blood with less effort.</li><li>Reducing avoidable cardiovascular workload through proper hydration is a simple way to support long-term heart health.</li></ul><p><br></p><p>The <a href="https://science.drinklmnt.com/electrolytes/the-whos-misguidance-on-sodium/" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">dominant narrative</a> around heart health often frames <a href="https://science.drinklmnt.com/electrolytes/is-sodium-good-or-bad" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">sodium as a blood pressure villain</a>. That story has been told so often it’s become accepted wisdom, despite the fact that it glosses over a lot of physiology and even more context (which we unpack in detail <a href="https://science.drinklmnt.com/electrolytes/salt-and-high-blood-pressure/" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">here</a>). </p><p>What gets less attention — and by that, we mean it’s rarely, if ever, discussed — is the impact of low-grade, day-in-day-out dehydration.</p><p>Now, to be clear: Temporary dehydration on its own is unlikely to cause heart disease. Over <a href="https://www.researchgate.net/publication/14606555_Dehydration_reduces_cardiac_output_and_increase_systemic_and_cutaneous_vascular_resistance_during_exercise" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">short periods</a>, the cardiovascular system compensates just fine. But when mild dehydration becomes chronic — even just <a href="https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31405195/" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">1–2% below optimal</a> — the cardiovascular system is forced to work harder, especially when paired with poor sleep, chronic stress, or inconsistent nutrition.</p><p>Think of it like running an engine that’s low on oil. It still runs — but wear accelerates. The system compensates until it can't.</p><p>And more people than you’d expect are walking around <a href="https://science.drinklmnt.com/electrolytes/dehydration-causes-and-symptoms" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">mildly dehydrated</a>. <a href="https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/12/4/905" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">Research</a> suggests that many adults consistently <a href="https://science.drinklmnt.com/electrolytes/dehydration-facts" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">fall short on fluid intake</a>, and that gap can add to your heart’s workload and compound over time.</p><p>Luckily, supporting heart health can start with a few easy wins and staying properly hydrated is one of the simplest to nail.</p><h2><strong>How Hydration Supports Heart Health</strong></h2><p>To understand why dehydration stresses the heart, you have to zoom out and look at the cardiovascular system as a whole.</p><p>“Our cardiovascular system is just one big, closed system with a pump in the middle,” says Savannah, GA-based cardiovascular surgeon and LMNT Partner <a href="https://www.drjeremylondon.com/" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">Dr. Jeremy London</a>. </p><p>Blood, which is about <a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279392/" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">90% water</a>, circulates continuously through a vast network of <a href="https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/21640-blood-vessels" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">blood vessels</a>, driven by a pump — your heart — which has two sides:</p><ul><li><strong>The right side </strong>receives blood returning through your veins and pumps it to your lungs to pick up oxygen.</li><li><strong>The left side </strong>takes that oxygenated blood and pushes it out to your organs, muscles, and other tissues.</li></ul><p>For that process to work efficiently, the heart needs enough volume coming back to it between beats. Hydration plays a direct role there. When fluid levels are adequate, the system runs smoothly. But when the reservoir runs low, the whole system is affected, says Dr. London.</p><h2><strong>How Dehydration Affects the Heart</strong></h2><p>Because your cardiovascular system is a closed loop, it’s extremely sensitive to changes in blood volume. When volume drops from dehydration, your heart and blood vessels have to work harder to maintain pressure and oxygen delivery. Those compensations help your body function normally in the short term, but they can come at a cost.</p><h3><strong>Short-term impacts: the immediate compensation</strong></h3><p>When fluid losses from sweat and urine aren’t replaced, <a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526077/" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">blood volume drops</a>. Your <a href="https://physoc.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.14814/phy2.14433" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">heart </a>fills more slowly between beats and <a href="https://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822%2816%2931344-6" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">pressure receptors</a> in blood vessels signal the nervous system to adjust output to keep circulation steady.</p><p>Your <a href="https://www.hri.org.au/health/your-health/lifestyle/hydration-and-your-heart" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">heart rate</a> rises to compensate, and your <a href="https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6723555/" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">blood vessels</a> constrict to maintain blood pressure despite the lower volume — which is exactly what they should do. The problem is when that compensation becomes the norm. </p><p>Early on, you may not feel much. But as dehydration deepens, signs of an overworked cardiovascular system can show up in a few tell-tale ways:</p><ul><li><a href="https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/9013-dehydration" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">Dizziness</a> or <a href="https://journals.physiology.org/doi/full/10.1152/japplphysiol.01217.2011" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">lightheadedness</a>, especially when standing up </li><li><a href="https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1728869X22000223" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">Heart racing</a> out of proportion to your activity level</li><li>Earlier fatigue during physical activity or <a href="https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1728869X22000223" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">workouts feeling harder than usual</a></li><li><a href="https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/muscle-spasms-muscle-cramps" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">Muscle spasms</a> or cramping</li></ul><h3><strong>Long-term impacts: when compensation becomes strain</strong></h3><p>When elevated heart rate and vessel constriction become the norm rather than the exception, it strains your cardiovascular system. These effects alone pose less risk than established factors like aging or obesity, but they can amplify those risks.</p><p>"Keeping your cardiovascular system in a constantly constricted state can increase the risk of high blood pressure, heart failure, and other conditions that can reduce quality of life and, compounded with other lifestyle choices, gradually strain heart function over time,” says Dr. London.</p><p>Over time, chronic dehydration may contribute to:</p><ul><li><strong>Impaired blood vessel function: </strong>Research suggests that even mild dehydration (about 2% of body weight loss) can impair <a href="https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00394-016-1170-8" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">how well blood vessels dilate</a> in response to changes in blood flow.</li><li><strong>Higher blood pressure: </strong>Stiffer vessels struggle to handle pressure changes. The result:<a href="https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10691097/" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank"> high blood pressure</a> that hardens arteries, which can further disrupt blood pressure regulation. It’s a vicious cycle. </li><li><strong>Lower </strong><a href="https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8267648/" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank"><strong>cardiac reserve</strong></a><strong>: </strong>If dehydration raises your resting heart rate, your heart has less capacity to respond to <a href="https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4914047/" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">additional stress</a> from exercise or severe illness.</li><li><strong>Heart failure risk: </strong><a href="https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/heart-failure/symptoms-causes/syc-20373142" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">Chronic strain </a>from risk factors such as high blood pressure, irregular heart rhythms, and narrowed arteries can damage or weaken your heart muscle. <a href="https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10263272/#abstract1" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">One large observational study</a> found that middle-aged adults with a marker of better hydration also had a lower risk of heart failure, though more research is needed to confirm a causal link.</li></ul><p><strong>Mild dehydration alone is unlikely to cause long-term damage to the heart “but when added into other lifestyle choices, it’s a real risk,” Dr. London says. </strong></p><p>Some heart disease risk factors — such as genetics and aging — are impossible to control. Many <a href="https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/healthy-lifestyle/lifes-essential-8" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">heart-healthy</a> habits — eating more whole foods, exercising regularly, sleeping seven to nine hours per night — can require substantial effort. In comparison, staying hydrated is relatively simple. “ I always say ‘get the easy stuff right.’ Stay well hydrated,” says Dr. London.</p><h2><strong>Why Electrolytes Are Essential</strong></h2><p>Water alone isn’t enough to keep enough blood pumping efficiently through your body. That’s because hydration and blood volume are related, but not the same thing. <strong>Drinking large amounts of plain water may increase blood volume, but without electrolytes, a large amount of this water may be rapidly excreted. </strong></p><ul><li><a href="https://science.drinklmnt.com/electrolytes/hydration" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank"><strong>Hydration</strong></a> refers to replacing fluid losses with water and electrolytes. </li><li><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526077/" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank"><strong>Blood volume</strong></a> is the amount of blood circulating in your vessels. </li></ul><p>When you drink water, it's absorbed through your gastrointestinal (GI) tract and enters your bloodstream. While water absorbs on its own, electrolytes — especially sodium — play a crucial role in how well your body uses that water.</p><p>Sodium enhances water absorption in the gut. But more importantly, it helps retain that water in your bloodstream where it's most useful for circulation and delivering nutrients to cells. Without adequate sodium, more of that water can shift out of your blood and into cells or the spaces between them.</p><p><strong>With adequate electrolytes on board, your </strong><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532305/" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank"><strong>heart rate can stay lower</strong></a><strong> and each heartbeat can deliver more blood with less effort.</strong> This matters most when you're sweating heavily, exercising, or losing fluids rapidly — times when maintaining blood volume is critical for performance and how you feel.</p><h3><strong>Sodium: the primary carrier</strong></h3><p><a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK591820/" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">Sodium</a> plays a central role in moving water from the GI tract into the bloodstream and keeping it there. The basic mechanism is osmosis: Water follows sodium across membranes because it's trying to equalize concentration on both sides. </p><p>When sodium is more concentrated in your blood than in your gut, water moves across the intestinal wall to balance things out — and stays in your bloodstream because that's where the sodium remains concentrated.</p><p>The right <a href="https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/hyponatremia/symptoms-causes/syc-20373711#:~:text=Sodium%20plays%20a%20key%20role,falls%20below%20135%20mEq/L." rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank" style="font-size: 14px;">sodium</a> concentration in your blood is also what supports circulation, nerve signaling, and muscle contraction.</p><p>Too little sodium, and water doesn't stay put in your bloodstream — it leaks into cells or tissues. </p><p>This is why hospitals give saline, <a href="https://science.drinklmnt.com/did-you-know/hyponatremia" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">not pure water</a>, in IVs for rehydration — the sodium keeps the fluid where it needs to be.</p>

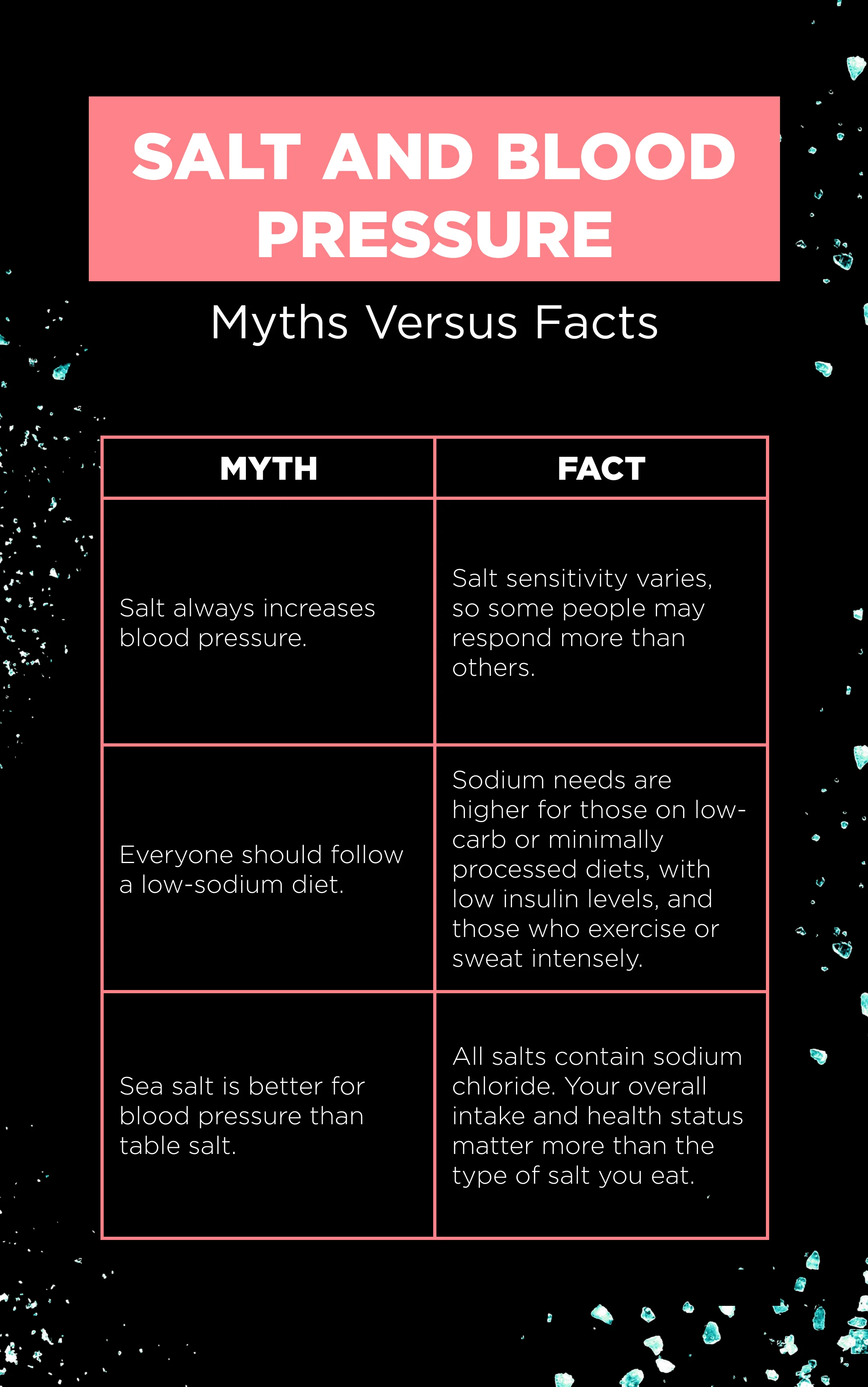

<h4><strong>What about sodium and blood pressure? </strong></h4><p>If you have healthy kidneys and normal <a href="https://science.drinklmnt.com/electrolytes/salt-and-high-blood-pressure/" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">blood pressure</a>, sodium consumed in reasonable amounts isn’t inherently dangerous. Your body will hold on to what it needs, and you'll just pee out the rest. </p><p>That said, people with high blood pressure, kidney disease, or a history of heart failure often need to be <a href="https://science.drinklmnt.com/electrolytes/salt-sensitivity" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">more careful with sodium</a>. But this isn't a static, forever status — it's interconnected with diet, activity level, and how you're addressing other risk factors. As your approach to health evolves (like <a href="https://science.drinklmnt.com/did-you-know/sweat-sodium-concentration" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">sweating more</a> or eating a primarily <a href="https://science.drinklmnt.com/electrolytes/sodium-deficiency/" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">whole foods diet</a>), so can your approach to sodium intake. </p><p>"If you don't have those things [high BP, kidney disease, heart failure], then giving your body adequate electrolytes and hydration based on your activity levels, and how much you sweat, makes total sense because sodium is so crucial for physiology in general,” says Dr. London.</p>

<h3><strong>Potassium: the blood pressure regulator</strong></h3><p><a href="https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16467502/" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">Potassium</a> works alongside sodium in many parts of the body, especially in blood vessels. While dehydration and sodium loss tend to narrow vessels, <a href="https://science.drinklmnt.com/electrolytes/does-potassium-lower-blood-pressure" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">potassium</a> helps them relax and widen, which supports healthy blood pressure.</p><p><a href="https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4332769/" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">Potassium</a> also affects how your kidneys handle sodium and chloride to help maintain healthy <a href="https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8819348/" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">blood pressure.</a> It also plays a role in regulating your heart’s <a href="https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/circep.116.004667" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">electrical activity</a>. When <a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482465/" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">potassium levels</a> drop — something that’s more likely when you’re dehydrated — it can throw your heart off rhythm.</p><h3><strong>Magnesium: the vascular smooth muscle relaxer</strong></h3><p><a href="https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8108907/" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">Magnesium</a> helps regulate vessel dilation and stimulates the production of substances like <a href="https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/apha.14110" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">nitric oxide (NO) and prostacyclin</a>, which tell vessels to relax. </p><p>When magnesium is low, the system loses margin for error. Your blood vessels tend to stay tighter than they should, which can push <a href="https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8108907/" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">blood pressure</a> higher and increase cardiovascular strain.</p><h3><strong>Calcium: your heart’s electrician</strong></h3><p>Calcium helps coordinate each heartbeat by regulating your heart’s <a href="https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/res.90.1.14" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">electrical function</a>. It also helps your <a href="https://www.nature.com/articles/415198a" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">heart’s muscle</a> cells contract to pump blood and expand to <a href="https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/circresaha.117.310230" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">refill</a>. Both too little and too much can disrupt normal rhythm and pumping efficiency.</p><h3><strong>Phosphate: the energy maker</strong></h3><p>Phosphate is needed to produce <a href="https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7599912/" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">adenosine triphosphate</a> (ATP), the molecule your cells use for energy. That includes the heart muscle, which depends on a constant supply of energy to contract effectively beat after beat.</p><p>Low phosphate levels can weaken cardiac contraction, while chronically high levels are associated with stiffer blood vessels. Keeping phosphate in a healthy range supports both energy production and vascular flexibility.</p><h2><strong>Hydrate for Your Heart</strong></h2><p>Staying hydrated with both water and electrolytes reduces unnecessary strain on your cardiovascular system. It helps your heart fill more effectively between beats, supports efficient blood flow, and keeps blood vessels responsive rather than rigid.</p><p>On its own, dehydration isn’t likely to make or break heart health. But physiology doesn’t work in isolation. <strong>Layer dehydration on top of aging, poor sleep, chronic stress, and inconsistent nutrition, and the total workload adds up. Over time, those small stresses compound. </strong></p><p>There are many heart-healthy habits — proper nutrition, exercise, sleep, quitting smoking, nourishing healthy social relationships — and they require effort that’s worth it. But hydration is foundational, relatively easy to get right, and it supports every other system doing its job.</p><p><strong>The strength of the heart pump is a critically important factor for longevity</strong>, says Dr. London. Supporting that pump is an accumulation of small, consistent decisions — and staying properly hydrated is one of the simplest ways to reduce unnecessary wear over time.</p>

<h2><strong>FAQ </strong></h2><p><strong>Q: What are the warning signs that my heart is stressed from dehydration?</strong></p><p><strong>A:</strong> Key signs include lightheadedness when standing up, <a href="https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37960187/" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">higher heart rate and lower heart rate variability</a>, and earlier fatigue during workouts. If you experience chest pain, severe shortness of breath, or dizziness, seek immediate medical attention.</p><p><strong>Q: Can dehydration cause permanent heart damage?</strong></p><p><strong>A:</strong> Severe, acute dehydration can cause life-threatening disruptions to your <a href="https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK555956/" rel="noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">heart rhythm</a>. But one bout of mild dehydration is unlikely to cause permanent damage in an otherwise healthy person. However, when chronic mild dehydration combines with other factors, such as poor diet, lack of exercise, inadequate sleep, or chronic stress, then cardiovascular strain could accelerate and worsen. That's why maintaining proper hydration is a foundational but often overlooked aspect of heart health.</p><p><strong>Q: I've heard sodium is bad for the heart. Should I avoid it?</strong></p><p>A: Sodium is essential for cardiovascular function — so it’s not a matter of <em>no </em>sodium, but <em>how much </em>sodium. The answer depends on your current health status, diet, and lifestyle. Folks managing high blood pressure, kidney disease, or heart failure may need to restrict sodium under medical guidance. But if you have healthy kidneys and normal blood pressure, your body will naturally regulate sodium — keeping what it needs and excreting the rest through urine. Sodium needs can shift as your health evolves, too. What's right for you today may look different down the road as your diet, activity level, and other factors change.</p>